Investing in uranium in Kazakhstan: navigating growing geopolitical risks

A deep dive into the country producing 43% of the world's mined uranium

In natural resource investing, gains are often made going to countries that other people couldn’t spell. The strategy isn't about investing in nations with lengthy, complicated names—although Kazakhstan fits this description—but rather about acquiring stocks from companies based in lesser-known or riskier jurisdictions. Ask your average Western investor if they would be willing to buy companies from the emerging markets, and it is probably a big no. In fact, many of them freak out at the mere mention of a country ending in “-stan”. I would argue that geopolitical risks are most of the time misunderstood or exaggerated by investors. As a result, some good companies are on a permanent sale.

Landlocked between Russia and China, Kazakhstan is de facto a geopolitical hotspot. The two giants it shares a border with aren’t the most friendly countries to Western investors. Nonetheless, for quite a while, Kazakhstan was considered the most stable regime in the post-Soviet space and attracted a lot of investments from the West. In addition to boasting the highest income per capita of the Central Asian republics, the country had experienced little civil unrest and political crisis compared to its neighbours. In 2023, I decided to see Kazakhstan with my own eyes and took a trip to Almaty, the largest city of the country. I was impressed by the cleanliness and modernity of the city. The standards of living seemed mostly on par with Eastern Europe.

However, the country experienced in 2022 its first major popular unrest. Rising gas prices and general discontent with the current regime pushed the Kazakhs to gather in the streets. What started as a peaceful protest in the oil-producing city of Zhanaozen quickly escalated into violent riots in major cities like Almaty, resulting in hundreds of casualties. The riots lasted less than two weeks, and things went back to normal after some concessions from the government. Albeit it left a profound mark on the Kazakh society. To us western investors, it also showed that the most stable country of Central Asia was perhaps not that stable.

The growing instability has also been fuelled by the war between Russia and Ukraine and growing geopolitical tensions. Kazakhstan’s commitment to remain neutral in the conflict complicated its relations with Moscow. The war also revealed the extreme dependance of its economy to Russian imports and exports, many of which are under international sanctions.

For investors, this new geopolitical context prompts for reconsidering investment strategies in the uranium sector. Fully understanding the risks associated is crucial not only for people invested in Kazakhstan’s assets but also for anyone invested in uranium in general.

First steps towards nationalisation

With its uranium reserves being some of the largests in the world, Kazakhstan has attracted many adventurous investors seeking opportunities in a critical commodity. As most know, uranium is essential for nuclear energy, which is increasingly recognized as a vital source of energy. Kazatomprom (KAP.IL), the national atomic company, has been a focal point for these investors. Additionally, the second-largest uranium producer in the world, Cameco (CCJ.TO), has a significant producing joint venture in Kazakhstan through the Inkai project. There are other foreign players with an interest in uranium mines across Kazakhstan, namely Orano (France), Rosatom (Russia), SNURDC (China), CGN (China), and CNUC (China). Although these state-owned companies are not publicly traded, their operations can indirectly affect the global uranium market due to supply dynamics. For instance, any disruptions to their operations could impact the availability of uranium worldwide, influencing the stock performance of Kazatomprom but also of Canadian and Australian equities.

Investors should not be surprised to learn that Kazakhstan has a history of government intervention in its energy sector. As in many authoritarian states, the Kazakh government has used legislation to increase its control over energy assets. As such, it has forced multinationals operating in the country to form partnerships with the state-owned entity KazMunaiGas. In the uranium sector, the government’s intervention has been so far less pervasive but the government’s 85% indirect stake in Kazatomprom stresses the state’s strong desire to run key energy assets.

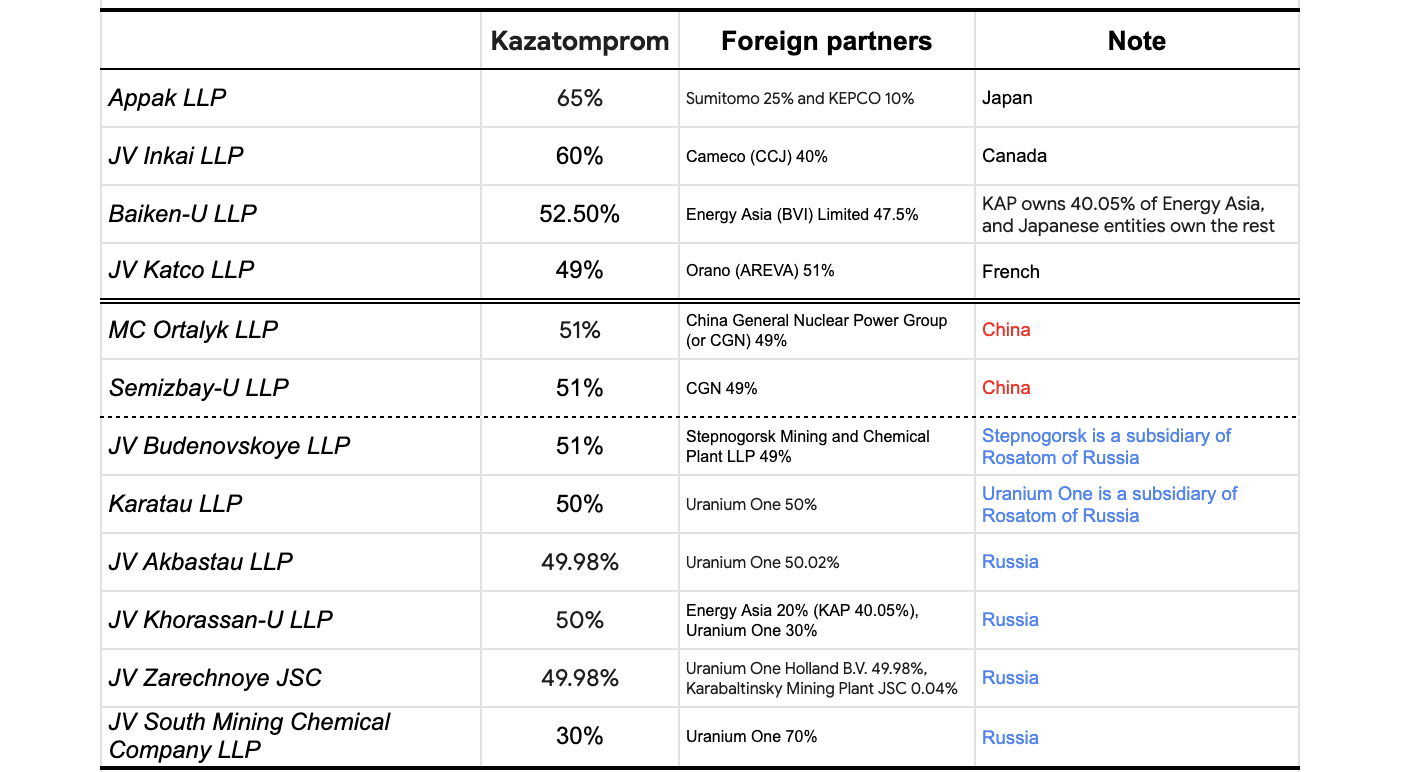

One form of interventionism was the enactment of a law requiring foreign companies to form joint-venture agreements with Kazatomprom should they want to mine uranium in the country. This is basically the Kazakh equivalent of the Chinese law requiring Western automotive manufacturers to form JVs with Chinese companies if they wish to produce in China. It is typical of how things work in the mining space, as local governments like to secure stakes in a project run by a foreign company for various strategic interests. Usually, this stake amounts to 10% or slightly more. But in Kazakhstan, the government has effectively closed the door on giving foreign actors majority ownership as reflected by Kazatomprom joint-venture ownership structures (KATCO and SMCC being two exceptions):

The indirect majority stake of the Kazakh government in the JVs implies for foreign miners a higher vulnerability to local political risks. Decisions on production quotas, profit-sharing, and even asset ownership often flow from the highest levels of governance. Operations are tied to strict terms tied to technology transfers or compliance with state priorities, which are both taken very seriously:

If a foreign partner fails to fulfill these expectations, resource access may be withdrawn, as then president Nursultan Nazarbayev reminded the head of Kazatomprom explicitly during a meeting in 2016. Two years later, when Kazatomprom’s Japanese partners failed to deliver on their promises of technology transfer, their shares in Kazakhstani joint mining ventures were dramatically reduced, and Kazatomprom took back control of the associated mining operations.1

And things could get more difficult for the foreign partners.

As reported by several local media in March 2025, the government is considering making amendments to the legislation to push for Kazatomprom to hold a 90% stake in JVs. The threat of a near-full nationalisation of the country’s uranium assets seems very real. Even though such amendments would only go into effect upon contract renewals, the rumours are worrying news for the foreign equities. They would be forced out of the country, losing high-quality deposits (Inkai accounts for about 18% of Cameco’s total production) to a competitor. Moreover, there is no guarantee of fair compensation for these assets. In theory, international law (UN Resolution 1803) allows for the nationalization of assets if fair compensation is given to the owners. In practice, the determination of what constitutes “fair compensation” can be subject to interpretation and may be decided by local authorities.

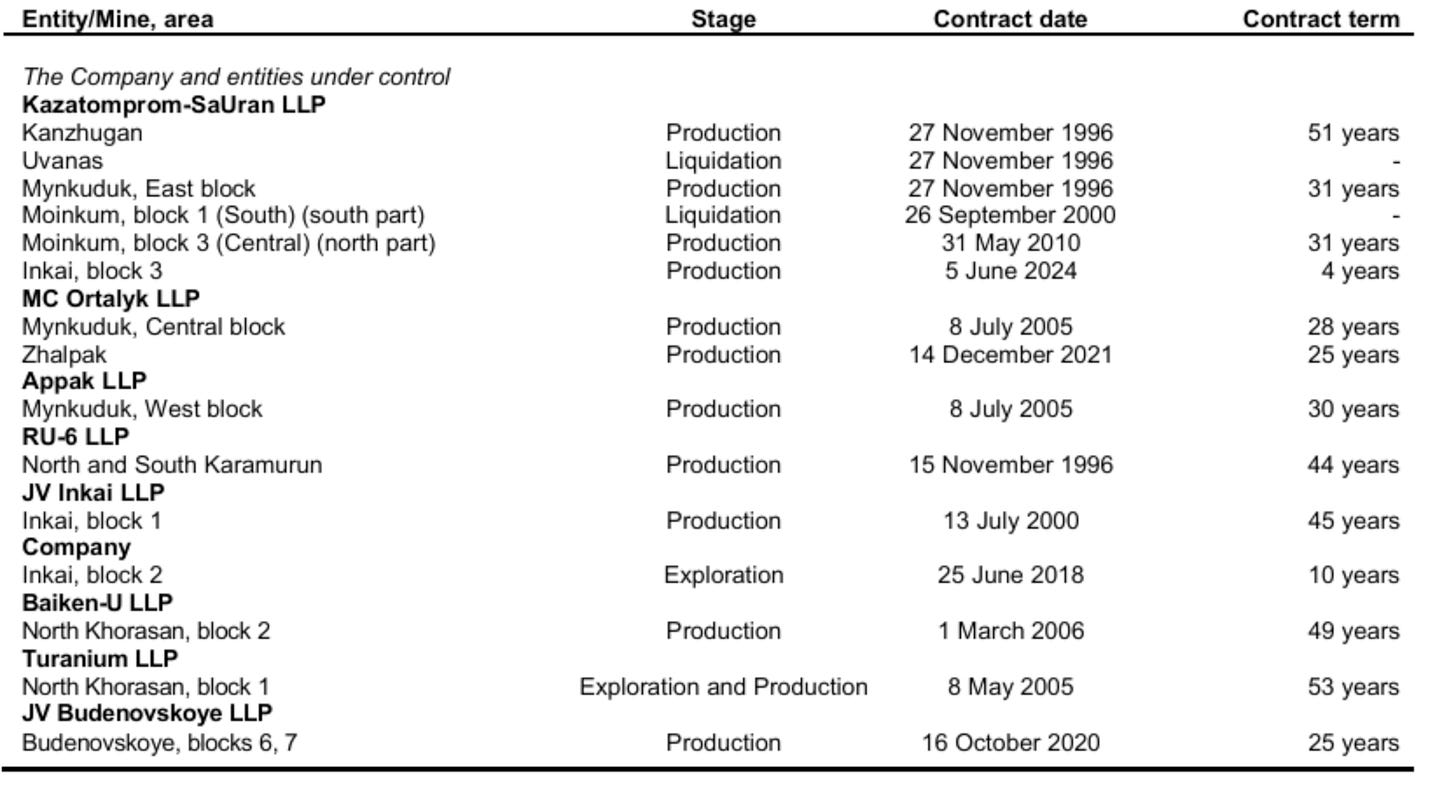

Based on the table below, Inkai block 1 is scheduled for renewal in 2045. But perhaps more concerning for Cameco shareholders, contracts block 2 and 3 are both expiring in 2028.

It’s hard for outsiders to predict what is going to happen next. But this new bylaw does seem like a first step in the nationalization of uranium assets. And as we covered in one of our recent articles, Kazatomprom has gone through extensive management turnover the last couple years, with many of the new appointed personnel coming from the public sector.

Supply chain issues and the Ukraine war

Kazakhstan’s geography is at the same time a curse and a blessing. The country is ideally positioned to export its resources, but is also stuck between two superpowers fighting for hegemony. For this reason, it is also of strategic importance for the West. The core of Kazakhstan’s foreign doctrine is a balancing act, managing the interests of its neighbours and the West. This is why investing in Kazakhstan is a complex exercise. One must understand the local politics and, on top of that, bear the strong geopolitical currents that influence the country.

One of them is the war between Russia and Ukraine. Despite not being involved in the conflict, Kazakhstan has been heavily affected by the international community’s answer to Vladimir Putin. Russia is Kazakhstan’s second-largest trade partner, and international sanctions on Russian entities have had a substantial impact on Kazakh operations.

Meirzhan Yussupov, CEO of Kazatomprom, has pointed out that sanctions caused by the war have created obstacles to supplying Western utilities. The cheap route via St Petersburg became impossible to use for Kazatomprom. Instead, an alternative route was established to ship the material through the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia and the Black Sea. Not only is this route lengthier and involved several modes of transportation but it is also highly vulnerable to geopolitical disruptions. Particularly from Russia.

In 2024, Kazatomprom was also impacted by a shortage of sulphuric acid, a critical material of its uranium mining operations. Kazatomprom didn’t communicate the full reasons for the shortage but we believe that the procurement of the reagent was complicated by international sanctions on Russia.

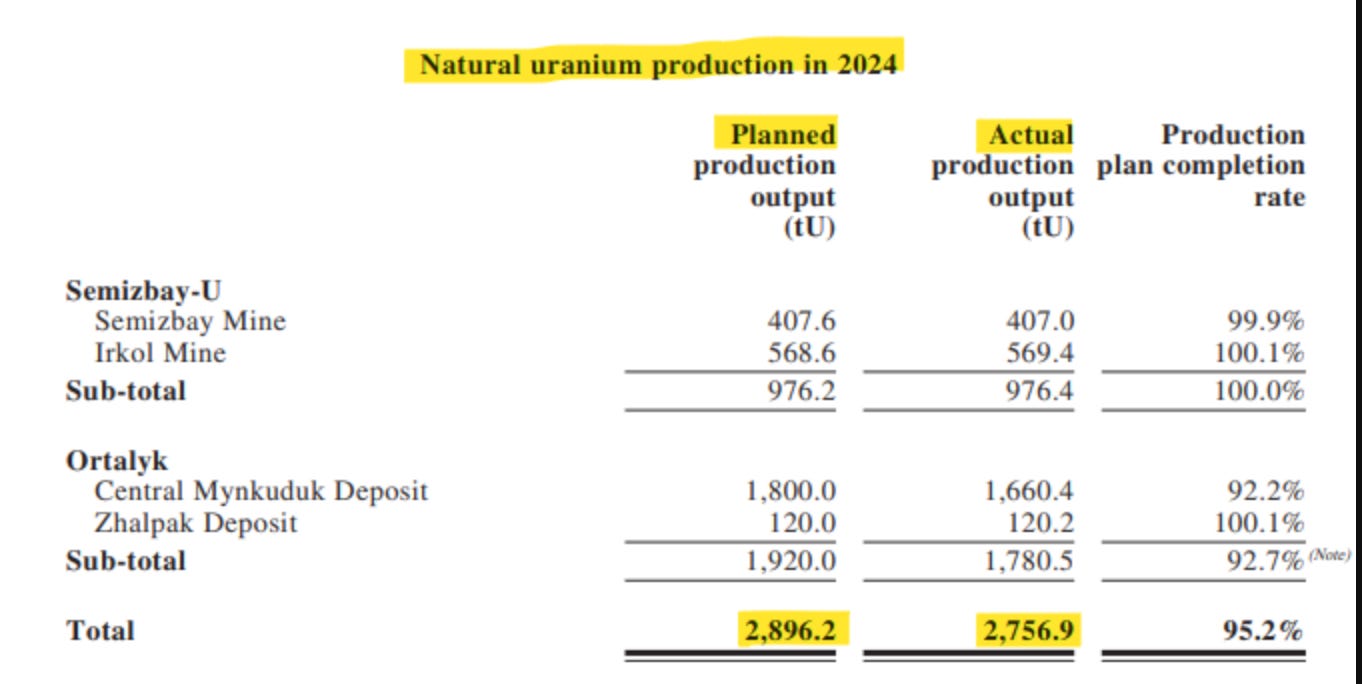

The discrepancy between the production guidance of CGN's (China) JVs and Cameco’s (Canada) Inkai JV is quite telling. While Inkai’s production fell at 80% of its guidance for 2024 at 80%, JVs with CGNs were all able to meet their targets at 3 out of 4 mines:

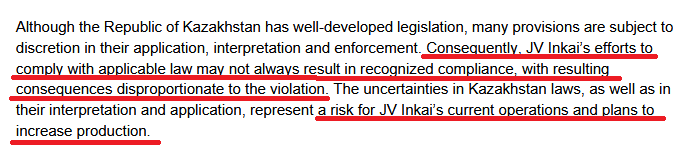

One theory is that CGN’s JVs were able to use Russian sulphuric acid while Cameco was not able to because of international sanctions compliance. China and Kazakhstan’s compliance efforts might not have matched those of the Canadian producer. This is what Cameco might have hinted at in one of their reports in 2024:

Regardless of future developments in the war, uranium producers in Kazakhstan will always be prone to the turbulence rising from Russia and its ideological rivals. And for every diplomatic trip Kazakh ministers make to Washington to discuss sanctions, they also engage in parallel efforts to reaffirm their alignment with Russia and Putin.

China: the (mandated) new bestie

China is now surpassing Russia as Kazakhstan’s primary trade partner, as it accounts for 19.2% of all Kazakhstani trade. Notably, Kazakhstan was the destination of Chinese President Xi Jinping's first foreign trip after the COVID-19 outbreak. Also, Kazakhstan's head Tokayev and Xi signed several agreements in May 2023 to strengthen their bilateral cooperation in many areas, including commerce, agriculture, and, importantly for us as uranium investors, energy. The two nations reached a trade pact to boost bilateral commerce from $41 billion to $80 billion by July 2023.

Additionally, Beijing is now working to improve Kazakhstanis' opinion of China, which has historically been rather weak, with a 2022 Central Asian Barometer survey showing that 70.5 percent of respondents had an unfavorable opinion of China. Now, the Kazakh government aims to improve Beijing's standing with the population. Tokayev even urged Kazakhstanis to put aside their worries of China in an interview in January.

Politically, China still considers itself a Third World country that sides with the developing world and does not align itself with any major power. It officially bases its foreign policies on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, but as part of its Belt Road Initiative (BRI), it has, in many cases, practiced what we call Debt-Trap Diplomacy. In short, China gives out excessive loans to highly indebted, low-income nations that are unable to pay them back. To reduce their debt load, these borrowing countries are then forced to give up strategic assets to China in a debt-for-equity exchange. As a result, China now owns important infrastructure, including ports and mines, as several countries, like Sri Lanka and several African nations, are not able to pay back their loans.

However, in terms of Central Asia, different nations are affected differently by China's debt-trap diplomacy. Notably, among Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan's debt to China is thought to be the most manageable. According to central bank data, as of January 1, 2024, Astana owed US$ 9.2 billion, primarily to the China Export-Import Bank (Exim Bank). However, this debt constitutes only about 3.5 percent of Kazakhstan’s gross domestic product (GDP). Turkmenistan, which depends on gas supplies to China, and Uzbekistan, which benefits from economic expansion, do not face significant challenges either. On the other hand, the Central Asian countries most vulnerable to China's Debt-Trap Diplomacy are Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Dept-Trap Diplomacy is not the only tactic that China uses to collect strategic assets abroad. While Kazakhstan has avoided Sri Lanka-style debt crises, its $31.5 billion trade reliance on China does create bargaining power asymmetry. For example, renegotiations over oil refinery projects such as Shymkent often favor Chinese equity stakes. Meaning, China also acquires resources through State-Owned Enterprises.

This took place in the uranium sector in December 2024, when China acquired a 49.99% stake in the Zarechnoye uranium deposit from Kazatomprom’s joint venture with the Russian mining giant Rosatom. Rosatom also partially withdrew from Khorasan-U. Further, Kazatomprom’s 2023/2024 contracts with China National Uranium Corporation (CNUC) and CNNC Overseas lock in China as the destination for ≥50% of its uranium concentrate exports. As a consequence, while freeing itself from Russian equity, Kazatomprom now relies on Chinese capital for 49% of its Ulba fuel fabrication plant and exploration licenses for four new deposits. On the other hand, the $2.5 billion+ from these recent deals helps fund Kazatomprom’s 2025 production expansion, ending its 7-year output curtailment policy.

For Kazatomprom itself, in view of its high national ownership stake, China’s growing influence in the country and its focus on key resources like uranium could be considered a net positive. The company is guaranteed to have a buyer for ~60% of its output, and China appears to help with the necessary infrastructure, too.

Despite the nationalization pressures we outlined earlier in this article, it looks like China will continue to acquire ownership stakes in Kazatomprom’s joint ventures, which could make it harder to model future financials, as the impact of these ownership changes is unknown.

These changing dynamics in Kazakhstan have implications for uranium investors. Decreased Russian influence in the country could be a good thing in light of the instability Russia causes. However, Western investors tend to discount stocks that are related to China, which could put pressure on Kazatomprom’s share price.

Geopolitical risks can be mitigated

All things considered, the geopolitical risk factor is closely tied to the company’s management ability to mitigate it. While some macro-risks may be beyond the control of management, mining companies have the power to influence decision-makers. The taxes, royalties, and social dues they pay make them highly valuable assets to the local governments. If management can effectively demonstrate this value (and to the right persons), then local governments might be more inclined to make their lives less difficult.

Evidence of that is copper producer Ivanhoe (IVN.TO). Ivanhoe can attribute much of its success to the incredible work of its founder, Robert Friedman, and its team in derisking its project in the DRC Congo, one of the most chaotic places on earth. If you follow the Kazakhstan route, ensure that the company’s management can handle the worst circumstances.

https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/03/to-secure-kazakhstans-uranium-chinese-players-were-compelled-to-accommodate-local-partners?lang=en